Changing the User model without breaking the crockery

How we switched from django.contrib.auth.models.User to a custom User model mid-project

Contrary to what some may think, there is science behind the trick of pulling the tablecloth from a table full of crockery, without making a major mess in the family’s porcelain heirloom. There’s not much scientific consensus, however, in the widely accepted notion that the trick requires skill, precision, and most importantly, courage.

Some situations in life, especially in software development, seem to resemble the tablecloth trick: one must change the foundation of considerable parts of the codebase without making the whole thing fall into pieces. Such is the case of changing the User model in a Django project that has been in production for some years.

In this blog post we’d like to tell you the story of how we succeeded in pulling the tablecloth trick with our User model at Alasco.

A glance at the past

In the pre Django 1.5 era, devs were forced to use Django’s definition of a user. For any customizations needed to the User model, devs needed to create a Profile model, make any desired customizations there, and then play along with the two entities bound together with a one-on-one relation. However Django 1.5 changed that for good, as its biggest selling point was a configurable User model that could be swapped in place of the old, rather inflexible User.

Customizable user models had been around for some years when Alasco was born. In retrospect it would have been nice to begin with a custom User model back then, yet the Profile workaround seemed more than enough for our use case at the time. Furthermore it actually proved to be scalable and very resilient for many years of intensive use in production.

Thinking of Django as of 2022, it’s only natural to do it in terms of a single model for storing all needed user information. Not because having a User-Profile approach represents a huge drawback in performance or code health, but because it’s cleaner, more extensible and makes developers happier. Therefore we embarked on the adventurous task of moving away from django.contrib.auth.models.User into our own custom User model.

Taking over the User model

Django’s documentation once leaned on the pessimistic side about changing a User model mid-project. At present however the official Django docs no longer make a case for any impending doom by doing so. An official guide for making the changes is nowhere to be found there, but rather a comprehensive set of steps is actually hinted, and can be promptly referred to in one of those long-lived threads of the Django ticket tracker.

So these are the steps we followed:

We first defined a custom User model identical in structure to that of django.contrib.auth:

from django.contrib.auth.models import AbstractUser

from django.contrib.auth.models import UserManager as BaseUserManager

class UserManager(BaseUserManager):

pass

class User(AbstractUser):

objects = UserManager()

class Meta:

db_table = "auth_user"The manager definition turned out to be important for us, as without it we started getting errors saying that User.objects couldn’t be used because the manager had been swapped out.

We then updated the setting AUTH_USER_MODEL to point to this newly created model. This was enough to swap the user in the entire codebase, because we were only referring to the User model through this setting or django.contrib.auth.get_user_model().

Next we did an exploratory step of regenerating our migrations from zero, only to examine and copy the operation that created the new custom user. We then restored our migration history and pasted the operation into the actual first migration of the app. Then removed all occurrences of migrations.swappable_dependency(settings.AUTH_USER_MODEL), and made the first migration depend on the most recent migration of django.contrib.auth, as explained in the unofficial guide.

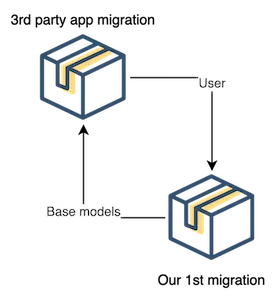

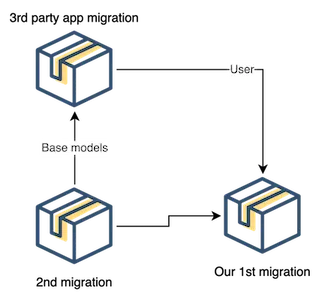

As warned by the Django docs, we ran into circular dependencies in migrations. This resulted from 3rd party packages depending on the User model, now defined in the first migration, which also depended on migrations of the 3rd party packages. Manually tweaking the migrations seemed daunting at first, but the solution was rather straightforward, as we only needed to move the operations and dependencies associated to the 3rd party apps into the second migration.

| Before: Circular dependency | After: Happiness |

|---|---|

|  |

After that we were able to run python manage.py makemigrations without any errors and without any changes being detected. We could also run all our migrations in an empty database and reach to the exact same state. The result in production was that we didn’t have to run any new migrations, or do any manual changes in the django_migrations table. Just what we needed!

One thing that we didn’t do from the guide was to repurpose the content type record of the former User model into the new one. It turned out to be an optional step for us, as we’re not making critical use of the content type machinery. We currently have two content type records in production, one for auth.User and another for our new User model. We might decide to merge them at a later time.

We could have also renamed the database table after the takeover, from auth_user to the default name of core_user. This is doable by just removing the db_table in the Meta options. However, we decided not to do so as of now, as that would have broken a number of queries we’re running in other external tools.

As a final touch of cleanup, we decided to start referring directly to our new User model, instead of doing it implicitly via settings.AUTH_USER_MODEL or django.contrib.auth.get_user_model(). While the abstraction had made the transition easier and is actually prescribed by certain section of the Django documentation, we had by then settled for the definitive User model, so we decided that we were not gaining any benefit from the indirection. Hopefully, we will not regret this decision in the future, otherwise, we will diligently write about it 😆.

Merging User and Profile models

The second part of our adventure was to merge the User and Profile models together, as we could then have all the extended fields directly in the User model. For the main part we only had to do a migration to transfer the data from one model to the other, after creating the fields in the new User model. In order to make sure that all fields had been copied over, we included an assertion like this at the end of our data migration:

from django.db.models import F

assert not User.objects.exclude(

field1=F("profile__field1"),

field2=F("profile__field2"),

...

fieldn=F("profile__fieldn"),

).exists()The assertion made sure that the migration was reverted if any field was different. This was only possible in the context of an atomic migration.

Additionally, we had to fix a number of foreign keys that were pointing to the Profile model, and replace them with foreign keys to the associated user records. We also had to make extensive corrections in our codebase to remove the dot access from user to profile, as well as the profile references from the select_related in our queries.

Fortunately, our codebase is extensively covered by tests, so it was rather easy to detect where we needed to make additional changes that had initially slipped from our view. Another plus to our comprehensive test coverage was that we were able to detect a slight reduction in the number of queries performed, as we had to fix our assertions for the number of database queries.

For the sake of the human process involved in making the code changes and peer-reviewing them, this second step was undertaken in a second moment after the first step.

Final thoughts

Even though the overall process didn’t turn out to be as scary as we initially thought, it is true that our morale was highly boosted by our levels of test coverage. Without proper tests, embarking in such a mission would have been extremely difficult to impossible, as there would have been no assurance that the app wouldn’t break from such massive changes.

A few words of praise must also go to Django itself.

The machinery behind the swappable models works so well, that we were a bit puzzled on how it was possible to have two different migrations (auth.0001_initial and core.0001_initial) both creating a User model, without one conflicting with the other. We found out that the trick lies in the swappable option of the user creation operation in auth.0001_initial, which renders the operation no-op when a custom user is detected in the project.

We continue to monitor any possible effects from the change, learn from the process, and plan new anecdotes.